She’s on the cover of the June/July 2013 issue of Harper’s Bazaar. She’s one of Fast Company’s most creative people of 2013. And she’s determined to stop women from dying in childbirth.

She’s on the cover of the June/July 2013 issue of Harper’s Bazaar. She’s one of Fast Company’s most creative people of 2013. And she’s determined to stop women from dying in childbirth.

Every day, roughly one thousand women die from the complications of pregnancy or childbirth, yet most of these deaths are preventable. That’s the message of model and activist Christy Turlington Burns’ documentary “No Woman, No Cry.”

The first-time filmmaker’s own experience with post-partum hemorrhaging after the birth of her daughter, Grace, and a 2005 visit to El Salvador, her mother’s homeland, inspired Turlington Burns to document maternal mortality worldwide.

“It’s a global tragedy,” she said at a screening of the film in New York City, so she decided to tell the stories of women in four different countries.

Turlington Burns first takes us to Tanzania, where a very pregnant Janet must walk five miles to reach a small clinic. She has no food with her, and the clinic provides none. Because her labor has not progressed enough, the health care worker sends her home. When Janet returns to the clinic, she’s so weak that she’s told she must now get to a hospital, a one-hour drive away. The van to take her costs $30, more than one month’s income for Janet’s family. Turlington Burns provides the money, and Janet gives birth to a healthy boy.

Tanzania lacks adequate health care facilities and medical personnel, as do most developing nations, with only one obstetrician for every 2.5 million people. With more and better facilities, women like Janet don’t need to die, as she surely would have if the film crew had not been there.

In Bangladesh, the issues are different. Health care facilities are often close by, yet most women will not use them because of the social stigma attached: it’s considered shameful to give birth outside the home. With proper education, however, attitudes can change. When a health care worker counsels Monica, who is ashamed to seek medical help, she finally agrees to have her baby in a hospital, leading to a happy outcome – the birth of a son.

In Guatemala, Turlington Burns encounters yet another issue. Abortion is illegal, even in cases of rape and incest. So when a young woman becomes pregnant as a result of rape, her illegal abortion almost kills her; it takes nearly six weeks of hospitalization for her to recover. Changing religiously based norms is probably the toughest challenge regarding maternal health, but it can happen, Turlington Burns argues.

Although 99 percent of childbirth-related deaths occur in the developing world, the United States has vast room for improvement, ranking 50th in maternal mortality. Women of color are especially vulnerable, as are those who have no health insurance.

“Being uninsured and pregnant is a disaster,” said Jennie Joseph, a Florida midwife featured in the film.

Ironically, the only woman who dies of childbirth-related complications in the documentary is an American woman who succumbs to an amniotic fluid aneurism. Turlington Burns shows the toll her death takes on her family with sensitivity and compassion.

Two years in the making, “” can be purchased on iTunes and Amazon.

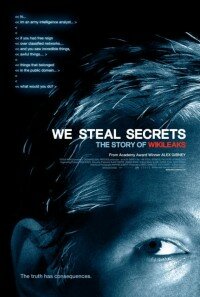

If you’re looking for a Michael Moore style documentary where you know the good guys from the bad guys, then this movie is not for you. While the first fifteen minutes appeared to detail the heroism of Julian Assange against the misdeeds of the U.S. government, the following two hours depicted a far more complex reality in which people may do the right things for the wrong reasons, or the wrong things with laudable goals in mind. Director Alex Gibney doesn’t give us a Moore fable or an Oliver Stone lesson in propaganda, but rather a complex study of an Icarus-themed Assange and a tortured but saint-like Private Bradley Manning.

If you’re looking for a Michael Moore style documentary where you know the good guys from the bad guys, then this movie is not for you. While the first fifteen minutes appeared to detail the heroism of Julian Assange against the misdeeds of the U.S. government, the following two hours depicted a far more complex reality in which people may do the right things for the wrong reasons, or the wrong things with laudable goals in mind. Director Alex Gibney doesn’t give us a Moore fable or an Oliver Stone lesson in propaganda, but rather a complex study of an Icarus-themed Assange and a tortured but saint-like Private Bradley Manning.