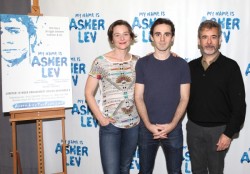

My Name is Asher Lev, playing at the Westside Theater in New York City, is about as close to greatness as any on or off-Broadway play is likely to get. Ninety-five minutes of mesmerizing acting led me to remember what a play is capable of. Although My Name is Asher Lev appears to be about a young Hasidic man’s desire to find himself in a community that doesn’t understand who he is, it is actually a universal story of a young man, perhaps a Jewish version of James Joyce’s The Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man. It is a coming of age story, a struggle against the father he loves but must disobey, love for his intercessor mother who positions herself between two warriors, and his finding himself in a sometimes hostile world.

My Name is Asher Lev, playing at the Westside Theater in New York City, is about as close to greatness as any on or off-Broadway play is likely to get. Ninety-five minutes of mesmerizing acting led me to remember what a play is capable of. Although My Name is Asher Lev appears to be about a young Hasidic man’s desire to find himself in a community that doesn’t understand who he is, it is actually a universal story of a young man, perhaps a Jewish version of James Joyce’s The Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man. It is a coming of age story, a struggle against the father he loves but must disobey, love for his intercessor mother who positions herself between two warriors, and his finding himself in a sometimes hostile world.

Specifically, it is the story of a “Torah-believing” Jew who has a hunger to paint in a community that believes art is a foolish waste of time.

With Ari Brand playing the lead, we don’t just observe his struggle, we feel it. We agonize over his love for his parents, his need to separate from and yet still be a part of them, and his desire to be an observant Jew in a gentile world.

Jenny Bacon, who portrays several different women, as Rivkeh Lev is so strong as the mother that when she also portrays the artist’s model, it feels a little incestuous. When she is about to disrobe so Asher can draw her, I was so invested in Asher that I was thinking, “Keep your robe on. It isn’t right to view your nakedness.” And Bacon’s portrayal of the gallery owner is so far removed from her other two roles that she seems a different actress.

Mark Nelson as Aryeh Lev is profound as the father struggling with love and duty to his rabbi and his son. Nelson’s portrayal of Asher’s painting tutor, Jacob Kahn, seems to embody the position that Asher’s father would love to embrace but can’t.

Rather ironically, Asher’s name in Hebrew means “happy.” In the Torah, he was a son of Joseph by a handmaiden, implying that Asher isn’t quite kosher. Some scholars suggest the tribe of Asher was descended from the Sea Peoples, one of whom were the Philistines. Rivka means “to bind,” and she is the one who keeps the family together. The father’s name, Aryeh, means “lion”, and he is a fierce protector and leader of his Hasidic community. As for the tutor’s name, Jacob was the one who struggled with an angel, and Kahn means “priest”, perhaps of the religion of art.

One of the great strengths of the production is that it gets you to feel it from the perspective of its characters. Few plays today do that. And unlike so many other current plays, like Grace, whose lead character is shallowly portrayed as a religious maniac, My Name is Asher Lev doesn’t belittle its characters.

In spite of the lead character’s continual struggle, this is a very hopeful play. This powerful portrait of an artist’s struggle inspired me to emulate Asher’s desire to become who he is really is.

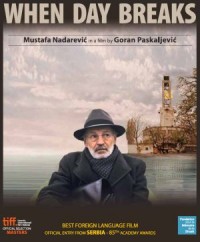

If tears aren’t rolling down your cheeks by the second half of When Day Breaks, then you aren’t fully human. This sad but passionate film tells the story of a mild-mannered and retiring (pun intended) music professor who must come to terms with the fact that his life as he knows it is a lie. Raised as a Christian in Serbia, he finds out he is a Jew who was given away by his parents at age two just before they were rounded up and sent to the Judenlager Semlin Concentration Camp in Belgrade.

If tears aren’t rolling down your cheeks by the second half of When Day Breaks, then you aren’t fully human. This sad but passionate film tells the story of a mild-mannered and retiring (pun intended) music professor who must come to terms with the fact that his life as he knows it is a lie. Raised as a Christian in Serbia, he finds out he is a Jew who was given away by his parents at age two just before they were rounded up and sent to the Judenlager Semlin Concentration Camp in Belgrade. My Name is Asher Lev, playing at the Westside Theater in New York City, is about as close to greatness as any on or off-Broadway play is likely to get. Ninety-five minutes of mesmerizing acting led me to remember what a play is capable of. Although My Name is Asher Lev appears to be about a young Hasidic man’s desire to find himself in a community that doesn’t understand who he is, it is actually a universal story of a young man, perhaps a Jewish version of James Joyce’s The Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man. It is a coming of age story, a struggle against the father he loves but must disobey, love for his intercessor mother who positions herself between two warriors, and his finding himself in a sometimes hostile world.

My Name is Asher Lev, playing at the Westside Theater in New York City, is about as close to greatness as any on or off-Broadway play is likely to get. Ninety-five minutes of mesmerizing acting led me to remember what a play is capable of. Although My Name is Asher Lev appears to be about a young Hasidic man’s desire to find himself in a community that doesn’t understand who he is, it is actually a universal story of a young man, perhaps a Jewish version of James Joyce’s The Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man. It is a coming of age story, a struggle against the father he loves but must disobey, love for his intercessor mother who positions herself between two warriors, and his finding himself in a sometimes hostile world.