Using Craigslist, my wife and I volunteered to be extras on a movie filming in the New York City area. We submitted a photo and our measurements. We both expected to play tourists visiting a restored nineteenth century village that uses costumed re-enactors. While she did portray a tourist, my fate was different.

Using Craigslist, my wife and I volunteered to be extras on a movie filming in the New York City area. We submitted a photo and our measurements. We both expected to play tourists visiting a restored nineteenth century village that uses costumed re-enactors. While she did portray a tourist, my fate was different.

We arrived on set at about 11:30 am and signed in with a bubbly young woman who was coordinating the extras. She told us she would try to have us in and out expeditiously. Of course, we waited and waited. We had been told there would be air conditioning, but as the outside temperature approached 100, all we had was two medium-sized electric fans for at least one hundred extras. We therefore decided to go out on the terrace, where the temperature felt at least ten degrees cooler. I had an inkling that something was about to change, when the extra wrangler approached us and told us to come inside and sit near her. She then told me I looked like “The Mayor.”

The wardrobe mistress fetched me and took me to a room where I had two choices of nineteenth-century-style wool jackets whose sleeves were a little long on me, one top hat that mysteriously fit perfectly, and a black cravat. She then sent me back to the hot-box holding room.

A half hour later she came for me again, gave me my clothes, and told me to put them on. A half hour after that, the make-up woman did my face. I was now officially “The Mayor,” clad in three layers of clothing, trying to adjust to the heat. Then I was on call for what turned out to be the next five hours.

Putting on the costume metamorphosed my shy self into an outgoing, talkative personality. When I looked in the mirror, I appeared a little like Abraham Lincoln. The staff started calling me “Mr. Mayor.” Other extras asked me to pose for pictures with them. One star-struck guy wanted to know what other movies I had been in. A little girl kept giving tea and lemonade to “The Mayor.” Another extra who had brought his own outfit looked like Stan Laurel of the Laurel and Hardy comedy team of the first half of the twentieth century. He was a voice impersonator with a spot-on Bullwinkle and Yoda, and said he had been in more than 100 movies. The SAG-AFTRA actors, normally aloof from the non-union extras, treated me like one of them, sharing their stories with me. One sweet looking young woman had been an international karate champion and had qualified for the Olympics.

Finally, at about 6 pm, those in period costumes took a van to the outdoor area where filming was taking place. Everybody seemed to know my character, including the co-director and her assistants. I was “The Mayor.” I had my picture taken by an official set photographer and by an assistant director. My actual part was fairly small. I was to wave, tip my hat, and greet visitors entering and leaving the park. While I assumed we were filming a comedy, I actually have no idea if my assumption was accurate. When the two stars passed by me, one of them started exaggeratedly bowing to me, which I returned in kind. Through the five takes, it became a game between us.

As we were returning to holding, all the extras, including my wife, were told they could go, except for those dressed in period costumes. The staff at holding hadn’t gotten the message, however, and some told us we could leave as well. I had to inform them we were asked to wait. Finally around 8 pm as the sun was starting to set, all of us, including my wife who had to stay because of me, were summoned back to the set for the last scene to be shot at the park. My job was similar to the first scene, except I was to thank people for visiting. Because of the lack of time almost no one was able to exit and I would be surprised if I were in frame in the scene.

In most movies the stars are off limits to the extras. You’re not supposed to talk with them or have any contact with them, including eye contact. This time was different. The two stars, who are household names, graciously allowed their pictures to be taken with some of the extras. As “The Mayor,” I was allowed to cut in line to do so with one of them.

I didn’t want to give back my costume, as it had somehow made me other than I was. I had been magically transmuted into a different person and energized. All in all, it was a pleasure for this usually skeptical observer of life, who is now smitten with the acting bug. In this one area, my wife is now more skeptical than I am about looking for more jobs as extras.

Somewhere in Darren Aronofsky’s more than two hour film is a great movie. With an almost impeccable performance by Russell Crowe as Noah – although not quite Oscar worthy, and a riveting performance by Ray Winstone as Tubal Cain, the film is part The Tree of Life and part Transformers. This schizophrenic coupling gives the movie an unsettling aspect. Fallen angels as stone monsters grapple with more lofty ideals of honor and responsibility to God and family.

Somewhere in Darren Aronofsky’s more than two hour film is a great movie. With an almost impeccable performance by Russell Crowe as Noah – although not quite Oscar worthy, and a riveting performance by Ray Winstone as Tubal Cain, the film is part The Tree of Life and part Transformers. This schizophrenic coupling gives the movie an unsettling aspect. Fallen angels as stone monsters grapple with more lofty ideals of honor and responsibility to God and family.

If you’re looking for a Michael Moore style documentary where you know the good guys from the bad guys, then this movie is not for you. While the first fifteen minutes appeared to detail the heroism of Julian Assange against the misdeeds of the U.S. government, the following two hours depicted a far more complex reality in which people may do the right things for the wrong reasons, or the wrong things with laudable goals in mind. Director Alex Gibney doesn’t give us a Moore fable or an Oliver Stone lesson in propaganda, but rather a complex study of an Icarus-themed Assange and a tortured but saint-like Private Bradley Manning.

If you’re looking for a Michael Moore style documentary where you know the good guys from the bad guys, then this movie is not for you. While the first fifteen minutes appeared to detail the heroism of Julian Assange against the misdeeds of the U.S. government, the following two hours depicted a far more complex reality in which people may do the right things for the wrong reasons, or the wrong things with laudable goals in mind. Director Alex Gibney doesn’t give us a Moore fable or an Oliver Stone lesson in propaganda, but rather a complex study of an Icarus-themed Assange and a tortured but saint-like Private Bradley Manning. House of Cards, a new mini-series on Netflix, never falls apart. This adaptation of a British TV drama, based on the novel by Michael Dobbs, stars multi-talented actor Kevin Spacey as Francis “Frank” Underwood, an oily Democratic majority whip, and Robin Wright as his wife, Claire, an unscrupulous non-profit head. The series is humorous and at the same time, very disturbing.

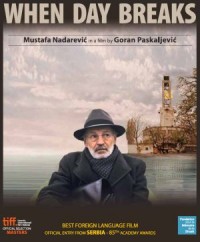

House of Cards, a new mini-series on Netflix, never falls apart. This adaptation of a British TV drama, based on the novel by Michael Dobbs, stars multi-talented actor Kevin Spacey as Francis “Frank” Underwood, an oily Democratic majority whip, and Robin Wright as his wife, Claire, an unscrupulous non-profit head. The series is humorous and at the same time, very disturbing. If tears aren’t rolling down your cheeks by the second half of When Day Breaks, then you aren’t fully human. This sad but passionate film tells the story of a mild-mannered and retiring (pun intended) music professor who must come to terms with the fact that his life as he knows it is a lie. Raised as a Christian in Serbia, he finds out he is a Jew who was given away by his parents at age two just before they were rounded up and sent to the Judenlager Semlin Concentration Camp in Belgrade.

If tears aren’t rolling down your cheeks by the second half of When Day Breaks, then you aren’t fully human. This sad but passionate film tells the story of a mild-mannered and retiring (pun intended) music professor who must come to terms with the fact that his life as he knows it is a lie. Raised as a Christian in Serbia, he finds out he is a Jew who was given away by his parents at age two just before they were rounded up and sent to the Judenlager Semlin Concentration Camp in Belgrade.